But pass the 11-plus I did, and I proceeded to Pinner County Grammar school in the September of 1946. This school was not far from Cannonbury Avenue and could be accessed through the grounds of Cannon Lane primary – so for another 7 years I went to school by the same route, through the Primary school and around the playing fields to the Grammar.

Many of my friends from Cannon Lane also went on to Pinner County, and I also made some new ones. I remember, however, being reluctant to move up from the first to the second year in September 1947 because I didn’t particularly like the boys in the second year! At the Grammar school it was stimulating to have different teachers for different subjects, and my favourite subject soon became Science, especially anything biological. Our Form mistress in class 1C was a young lady newly graduated from Durham University. Since she had an accent appropriate for that region, I thought that she must be ‘foreign’ and told my parents that she was ‘Swittish’ - about as foreign as I could imagine! Another teacher, who had stood as a Communist candidate for Southall in the 1945 election (and lost his deposit) entered the classroom and announced that ‘army discipline’ was the order of the day. Discipline almost immediately broke down and was never fully restored!

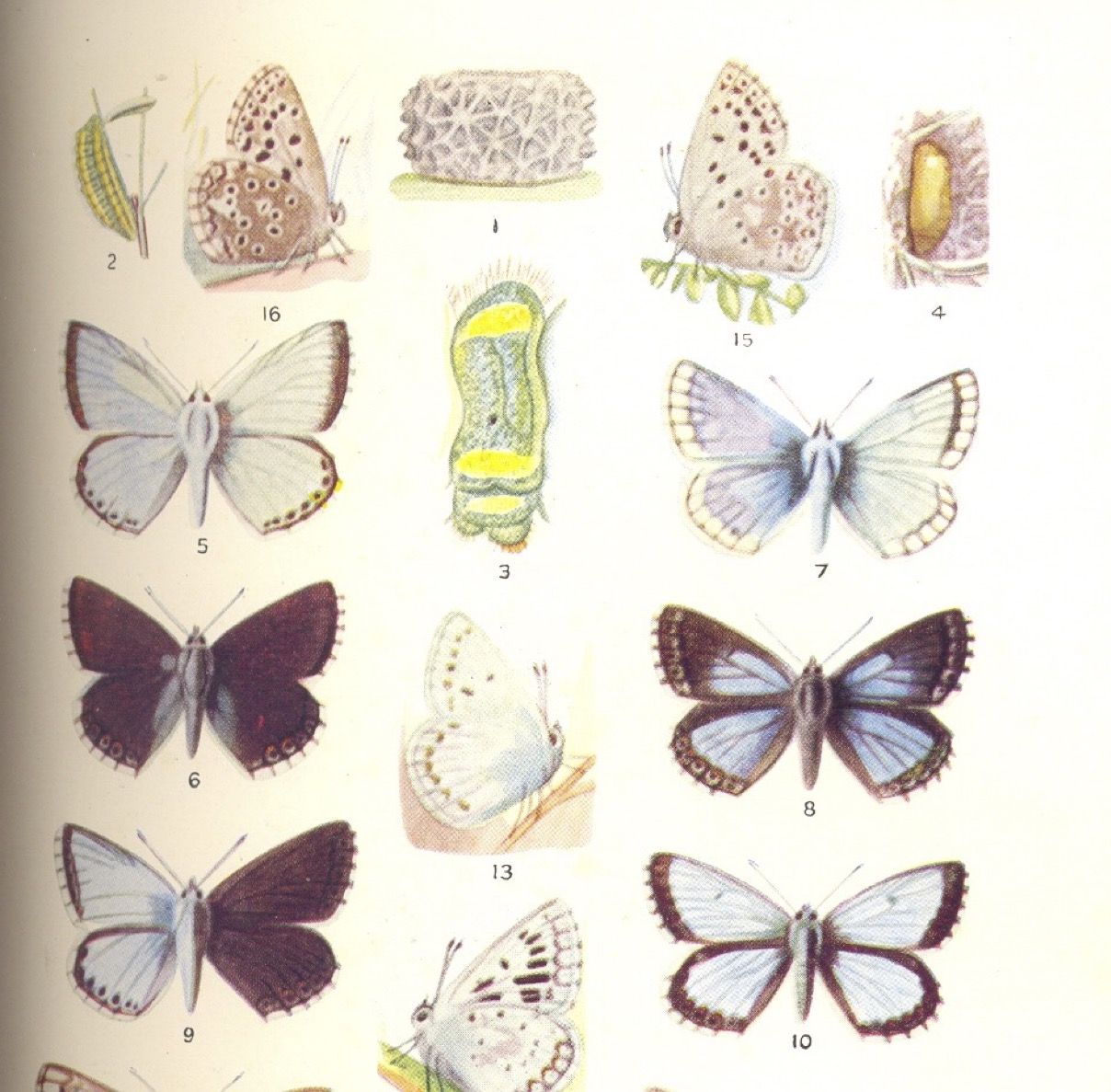

Biology became my favourite subject at school because my father gave me one of the greatest gifts, a love of nature. My father had an encyclopaedic knowledge of wild flowers and insects, especially butterflies, having collected them since the 1920s with his brother, David. Together, throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, my father and I roamed the countryside as far as Surrey, north Kent, the South Downs, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire in search of our quarry, and family holidays were spent in localities such as Dorset and Cornwall where prize specimens might be expected. We went to Salcey Forest in Northamptonshire to hunt the elusive Purple Emperor (Apatura iris), to the South Downs and to Royston, Cambridgeshire to look for ‘varieties’ of the Chalk Hill Blue (Lysandra coridon) and to Cornwall to seek the Large Blue (Maculinea arion). I am pleased to say that we failed to find any of the latter, which were (and still are) a threatened and protected species. On one visit to the Lucerne fields near Broadstairs to collect specimens of the Clouded Yellow (Colias croceus) and the Pale Clouded Yellow (Colias hyale) as they arrived from France, we lost our ‘killing bottle’ in the undergrowth. Becoming agitated, my father said that the bottle contained enough cyanide to kill half the population of England! However, after several hours of hunting we found it - so avoiding mass extermination of the population. At home, we reared caterpillars in cages in the back garden, and made nocturnal visits to the local woods to catch moths attracted to the light of a Tilley lamp or to sugary concoctions painted on the trees. By the time I was 12 years of age I knew the Latin names and habits of all the British butterflies, and many of the moths. My favourite ‘lavatory reading’ at that time were the two volumes of Richard South’s The Moths of the British Isles which I had been given for passing the 11-plus.

My father’s other enthusiasm which he transmitted to me at this time was his love of cricket. He was a Man of Kent, being born at Ringwould, near Deal, and educated at the Harvey Grammar School in Folkestone, along with Les Ames who eventually became the Kent and England wicketkeeper and all-rounder. Although I have never lived in Kent, I remain a life-long supporter of that county’s fortunes rather than that of Middlesex, the county of my birth.

My father’s support and encouragement for my developing interests in entomology were extended in early 1950 when he arranged for us to visit Dr C. B. Williams, a leading entomologist at Rothamsted Experimental Station near Harpenden in Hertfordshire. In reply to my father’s initial letter, Dr Williams wrote:

“Dear Mr Saunders, in reply to your question about a career in Entomology for your son, we have at Rothamsted and at similar Research Stations three grades of assistants…. I think it will be clear to you that everything is to be gained by a boy having the highest possible educational qualifications”

When we went up to Rothamsted that spring, Dr Williams told us that the lower grade of entomological assistant could in time reasonably expect a salary of £400, and as much as £1,000 a year for a scientist with a good degree and a research qualification. Clearly there was a lot for me to aim for. Years later (1955) I met Dr Williams again after his retirement to Kincraig in Inverness-shire, where he was collecting moths of the area at a light trap. He asked me to help with the identification of some of these moths but was clearly disappointed that I had forgotten so much since my days hunting bugs with my father.

The Chalk Hill Blue, Lysandra coridon, and some ‘varieties’

In 1948 when I was 13 my parents gave me my first ‘proper’ bicycle, a blue and chrome Dawes. This opened up my horizons immensely and, together with friends I started to explore the local countryside. Early in 1949 my friend Brian Huggins and I joined a local cycling club, the Northwood Wheelers, and for the next seven years or so cycling became a way of life for me. My cycling activities were recorded in a series of diaries from 1950 to 1955 which are now available on the web (The Northwood Wheelers), and which lists every trip taken, every mile covered and even every cake consumed. Apart from a period between about 1958 and 1975 when I was more concerned with raising a family and developing my academic career, I have been a life-long cyclist, now (in 2005) possessing seven bicycles and having covered over 140,000 miles, more than half the way to the moon! Details of this period of my life are to be found in the above web-pages; only certain highlights will be included here.

On an early cycling trip: Stockheath youth hostel, Hampshire, 1st July 1949

In the Northwood Wheelers I was soon drawn into the sport of Time Trialling, the first way that Time became an important aspect of my life. In time trials, competitors ride as fast as possible over fixed and carefully measured distances (10, 25, 50 or 100 miles) on out-and-home courses, or as far as possible for 12 or 24 hours. I rode all events up to 12 hours but never had the bottle for a ‘24’! I was never a great athlete, but rather a competent ‘club’ performer. I was clearly better at the longer distance events, having more stamina than speed, and became club champion several times over 100 miles, and took the club record for 12 hours at 225 miles and 1,661 yards. This was quite a respectable performance in 1954: it would still have earned me 25th place in the 2004 National Championships, half a century later.

An early adventure occurred in the summer of 1951 when Brian Huggins and I (both 16 at the time) rode from home to Dundee and back, 1,392 miles in 27 days, all at a cost of £15. 15s! Our northward journey took us up through the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales, over to Whitby, up through Northumberland and the Borders to Edinburgh and Stirling. On our return journey we crossed the Kingdom of Fife and cycled through the Lake District, parts of Wales and home through the Cotswolds. That was only one of a number of long trips taken by bicycle, culminating in a solo tour of the Scottish Highlands in 1955.

Just before we set off on our trip to Dundee, Brian and I were among the first to sit the new Ordinary Level examinations. We were very much the ‘guinea-pigs’ since students the year before had sat the old Schools Certificate. After some private coaching in English and French, I managed to obtain passes in five subjects; I can’t remember what I flunked. In the September of 1951 we returned to Pinner County School in the Lower Sixth, where I undertook studies in four Science subjects, Physics, Chemistry, Botany and Zoology. I found Physics to be difficult and dropped it at the end of the year after obtaining an O-level in that subject. This left me with three subjects to carry on through the Upper Sixth to Advanced Level. The two Biological subjects were well taught and, at last, I came into my own. I also much enjoyed Chemistry at this stage. It was taught by an endearing Austrian Jew called Dr Liebenmann, who was a refugee from the Nazis. At assembly one day the headmaster announced that Dr Liebenmann was leaving. The whole school gasped. Then the headmaster announced that he was to be replaced by a Dr Linton. It turned out that Dr Liebenmann had become naturalised and had merely anglicised his name! Apart from Chemistry he taught some of the older boys the rudiments of German, which put us in good stead when we went on to University because Ph.D. programmes at that time still had a requirement for candidates to translate a passage in a foreign language, usually German which was still considered to be the language of Science.

Although in the Sixth form I seemed to find scholarly form, I always played second fiddle to the class brain-box, Laurence Plaskett, who eventually went up to Clare College, Cambridge, to read Biochemistry. When the A-level exams arrived in the summer of 1953, however, I surprised myself (and probably the school) by getting good passes in Chemistry, Botany and Zoology, and a State Scholarship in the last two. Consequently my name was carved on the school Honours Board. Pinner County Grammar school, however, closed in the 1970s as part of the Comprehensive revolution and became, for a short time, a local Sixth Form College. I have no idea what became of the Honours Board, or the evidence that I ever achieved a State Scholarship!