Although the time of my retirement from the University was fast approaching, my laboratory in Edinburgh remained active and lively. During the early and middle of the 1990s Bob Lewis and Bron Cymborowski made research visits, and a number of good Ph.D. students, including Sean Gillanders, Seau-Feng Hong and, latterly, Harriet McWatters worked in my group. Their work will be described in this section.

In the summer of 1995 I took part in the fourth Erasmus Summer School held that year in an Italian mansion high in the hills above Florence. This was the first of the ‘new-style’ summer schools, lasting for just one week, instead of the four weeks of the earlier meetings in Groningen, Frankfurt and Edinburgh. The students only attended lectures by visiting ‘experts’ and did not carry out a research project. This change came about because of difficulties in raising sufficient money for a full month’s course, and of difficulties the students encountered in getting away from their own research programmes for that length of time. After the summer school ended, many of the teachers moved on to the Gordon conference, held that year for the first time in Europe, in Barga, near Lucca. The conference was high in the hills above Barga, the mountain road to the rear of the conference centre being part of that year’s route for the Giro d’Italia. Unfortunately, the conference did not coincide with that great race! I did, however, manage to collect a specimen of Calliphora vicina to add to other geographical strains of that species for a study on latitudinal variation of photoperiodic time measurement and cold tolerance being conducted back in Edinburgh. That single fly – fortunately, an inseminated female - was carefully taken back to Scotland and became the foundress of our ‘Barga’ strain, whose characteristics will be described later.

Later in 1995 Jean and I flew to Boston and then hired a car to drive up to Dartmouth Medical School at Hanover, New Hampshire, to attend a conference on Biological Clocks organised by Jay Dunlap. The idea behind this conference was to gather most of the recognised authorities on the various aspects of Chronobiology, ultimately to produce a multi-author text-book suitable for advanced students reading this subject at university level. The meeting itself was a great success, but the publishing venture fell upon rather stony ground with many contributors failing to deliver their contributions, or even backing out of the project altogether. The book finally appeared in 2004 as Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping after a lot of hard work, mainly by Pat DeCoursey.

To get to the meeting we travelled north from Boston airport following the route I had made in 1989 to that year’s Gordon conference, staying in a motel close to Lake Winnipesaukee and then driving over the White Mountains. At Dartmouth we stayed in some style at the Hanover Inn. After the conference we crossed into Vermont and then drove south to re-enter Massachusetts near the little town of North Adams. We then travelled across Massachusetts, through Amherst and Worcester, and back to the Boston area where we paid a visit to Jeff Hall and Mike Rosbash at Brandeis University. Here we met the students, and drank beer with them, but very little Science was discussed, unlike any of my earlier visits to the laboratories of fellow chronobiologists. Perhaps that is the way molecular biologists guard their secrets, by holding their cards very close to their chests! Since this was the whole point of the visit, this was rather a disappointment! The next day we flew back to the United Kingdom.

Back in Edinburgh, work on Calliphora and Drosophila continued. Using his surgical skills, Bron Cymborowski showed that the optic lobes of adult Calliphora were unnecessary for the photoperiodic induction of larval diapause, just as they were for circadian expression and entrainment. This focussed attention on the brain as the anatomical location for both the photoreceptors and central ‘clock’ mechanism involved in photoperiodic timing. On one of his visits he also brought with him a sample of an antibody raised against arrestin (S-antigen), an important protein in the phototransduction ‘cascade’. Together with Feng and Harriet, we showed that injection of this antibody into the brain of adult Calliphora appeared to reduce the effects of light. For example, in flies exposed to a light cycle (LD) entrainment sometimes failed, and in flies exposed to continuous light (LL) some of them continued with a free-running period instead of the expected arrhythmic behaviour. In her Ph.D work with Calliphora locomotor activity rhythms, Feng worked on the effects of LL and the phase-shifting effects of temperature steps (up and down); she also produced good evidence for the complex, multi-oscillator nature of the central pacemaker.

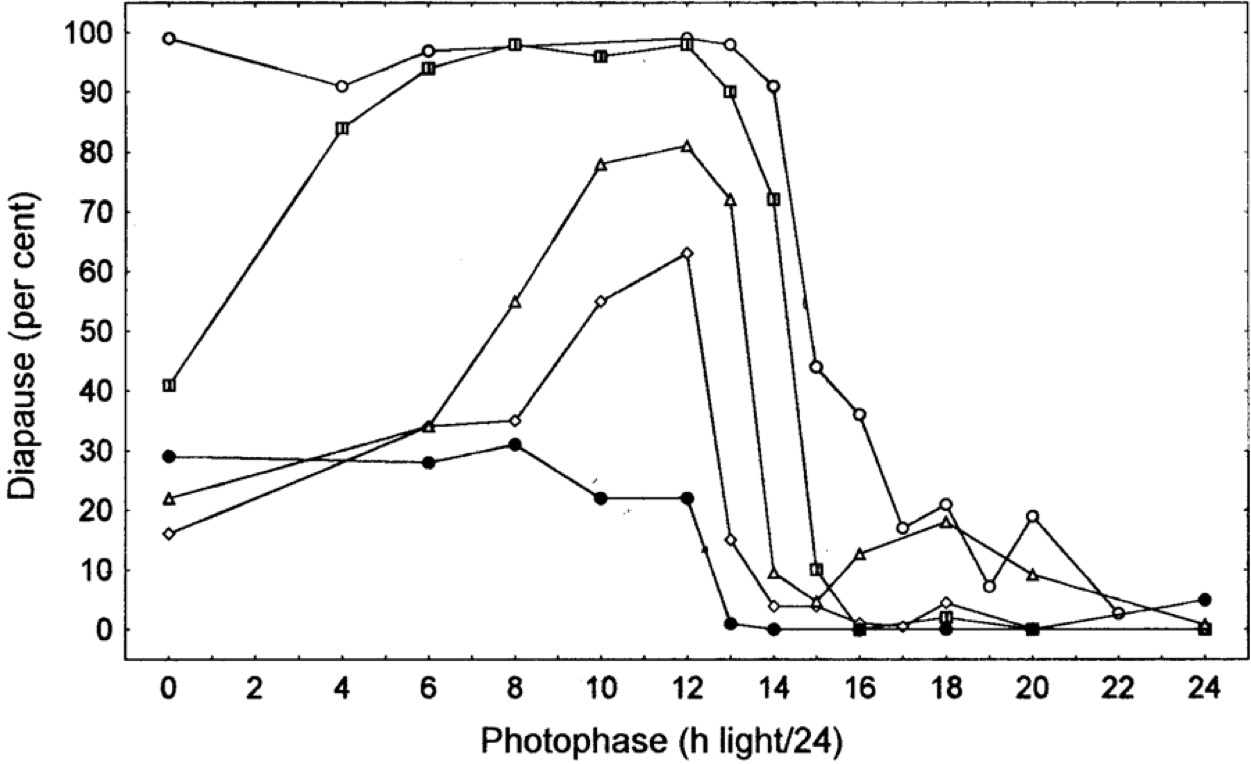

A number of geographical strains of Calliphora were established in the laboratory. The most southerly strain was Barga (44 °N) derived from the single inseminated female brought home from Italy. A second strain was collected by Jim Hardie at Silwood Park, Ascot (51 °N) and a third by Pekka Lankinen from Nallikari (65 °N) near Oulu, northern Finland. These strains joined that collected locally (Edinburgh, 55 °N) and together they spanned a large part of the north to south latitudinal range of this species in Europe. In addition, I had collected flies from Chapel Hill (36 °N) whilst on sabbatical in North Carolina. Various parameters of photoperiodic diapause were studied. As expected, the ecologically important critical day length was longer in strains from the north than in those from the south, and more northerly flies showed a greater incidence of diapause under any one short day. The diapause so induced was also more ‘intense’, or longer lasting, in flies from the north. Work with Scott Hayward showed that northerly strains were more tolerant of the cold (0, -4 and -8 °C), especially as diapause-destined and diapausing larvae. However, when diapausing larvae of Nallikari, Edinburgh and Barga were kept in the same constant conditions (darkness and 11-12 °C), rates of water loss and of fat metabolism were identical. This meant that flies of the Barga strain with its relatively short diapause emerged with greater residual fat reserves than flies from Edinburgh or Nallikari. It was concluded that the rates of water and fat loss were functions of the conditions experienced during diapause (probably temperature) rather than the maternally programmed degree of diapause incidence, or of its ‘depth’ or ‘intensity’. At the lower soil temperatures experienced by the over wintering larvae in their natural habitat, fat reserves would clearly be sufficient to see them through to the spring.

Photoperiodic responses of Calliphora vicina from various localities. Right to left: Northern Finland, 65°N, Edinburgh 55°N, Barga 44°N, London 51°N and Chapel Hill 36°N, all at 20°C.

Using flies from the Nallikari and Silwood Park strains, Harriet investigated genetical aspects of the photoperiodic response in Calliphora. In crosses between the northern and southern strains, she showed that the incidence of diapause and the critical day length were maternal characters, the males playing no part in these aspects of the diapause response in their immediate offspring. The duration of diapause, however, was a larval characteristic. Thus, larvae with mothers of the northern strain and southern fathers entered diapause at the same rate as pure bred northern larvae but emerged from it much more quickly. Diapause duration, therefore, is a characteristic of the larvae themselves, influenced by the genetic background of both parents. In a later paper, Harriet showed that hybrid female offspring between Nallikari and Silwood flies were not intermediate between the two parental strains but showed a photoperiodic response biased towards their maternal line. Thus not only are the males unable to directly influence the diapause incidence among their immediate progeny, but the indirect effects of inheritance down the male line are weaker than down the female. On the other hand, diapause lasts longer in larvae with a greater proportion of northern genes, regardless of whether they were maternal or paternal.

My own research showed that diapause-destined but under-sized larvae of Calliphora, produced by severe overcrowding within their supply of food, side-stepped the diapause programme to become small adult flies. It was shown that these under-sized individuals, although containing the same proportion of fat as their full-sized siblings, were less cold tolerant. It was suggested that if warm autumnal temperatures together with a high fly density led to larval overcrowding within limited resources, larvae diverted from their diapause pathway could become, albeit small, reproductive adults. The trade-off here is that larger larvae with ample reserves enter diapause and have a high chance of winter survival but forfeit the possibility of further reproduction before the winter sets in. On the other hand, small larvae from overcrowded conditions, with a higher metabolic rate and less fat, would not survive the winter, but by diverting from the diapause pathway give themselves an opportunity to breed again.

As Head of Institute I was called upon to give the opening address at several conferences in the Edinburgh area. These included the International Conference on Insect Pests in the Urban Environment (1996), the 17th European Colloquium of Arachnology (1997) and a public lecture for the Edinburgh International Science Festival (1997) on How Animals Tell the Time. I also went to several more exciting destinations, sometimes travelling with Jean as part of our annual ‘holiday’.

In 1996 I was invited to Eugene, Oregon, by Bill Bradshaw to give a lecture on Drosophila diapause and photoperiodism. I first flew out to San Francisco where I stayed with M.F. Bowen and her husband James, who were by then living in Oakland. I then continued on to Eugene. Bill Bradshaw, whom I first met at Harvard in 1970, had been conducting an in-depth study of diapause and photoperiodism in the pitcher plant mosquito Wyeomyia smithii for many years. This insect, whose larvae live within the small volume of water collecting in the pitcher plant Sarracenia purpurea – but avoid being digested – lend themselves to a laboratory study because they are predisposed to life within small containers. W. smithii occurs along the eastern seaboard of North America from Georgia to southern Canada. However, when Bill moved to the west coast he and his wife Christina Holzapfel continued to work on this insect, although I suspect that they secretly hoped that a similar ecosystem could be found in local insectivorous plants (Darlingtonia californica). Bill took me on a long trek near the Oregon coast to see these plants. After our return to Eugene I sank into a relaxing Jacuzzi bath and enjoyed a beer from one of Oregon’s excellent micro-breweries. My talk on photoperiodism in Drosophila melanogaster seemed to go down quite well, although I suspect that Bill was a trifle disappointed that my observations on the role of the period gene in this phenomenon had not progressed further. After a couple of days in Eugene, Jaga Giebultowicz came down from Corvallis to meet me. We returned to Corvallis for a day or two until I flew to San Francisco and then on home.

Insectivorous plants (Darlingtonia californica) in Oregon

The next important trip was one that Jean and I made to Israel and Jordan in September 1997. I had been invited by Larry Gilbert to give a talk at the International Conference on Invertebrate Neurochemistry and Neurophysiology to be held at Eilat, Israel. I was asked to give an overview of my work on Insect Circadian Rhythms and Photoperiodism. At first I was rather reluctant to go to Israel, but Jean pointed out a post-conference trip to Petra in Jordan, an opportunity that could not be missed. Because of the heightened security checks imposed by El Al on flights to Israel we were carefully checked at Heath Row before our flight to Tel Aviv. A rather fierce-looking young lady asked me whether I had ever been to the Middle East. When I answered - truthfully - “Yes: to Beirut”, consternation arose, until it was pointed out that that visit was in 1960, probably before she was born! On arrival at Ben Gurion airport we had to change planes, continuing to Eilat from another, smaller airport. The taxi driver seemed never to have even heard of this second airport and just continued to cruise around the streets of Tel Aviv as though completely lost until I spotted directions to the airport and we were able to continue on our journey on a small plane over the Negev desert to Eilat. Eilat seemed to be a rather soulless concrete town, but the meeting was good, the waters of the red sea warm, and the people friendly.

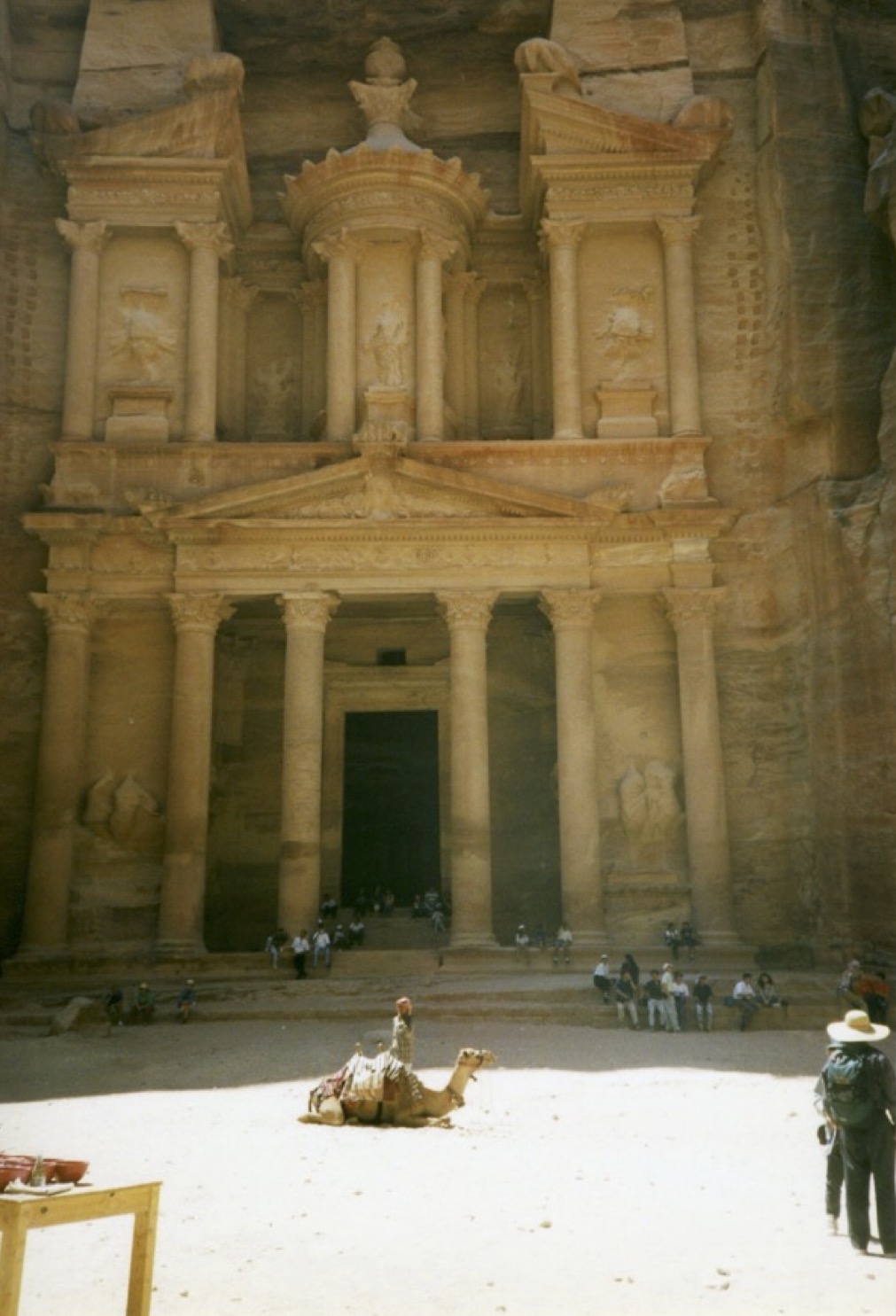

Improved diplomatic relations between Israel and Jordan in 1997 enabled us to make a visit to Petra. These relaxations, however, were far from complete and lead to a bizarre event on the border. With foresight, one member of our group bought some water in Eilat anticipating a hot and dusty drive up to Petra. However, when we reached the Israeli-Jordanian border she was made to empty the water down a drain, but then allowed to buy more water in the Jordanian shop on the other side of the line. Clearly, Israeli water was not allowed into Jordan!

After the anticipated hot and dusty drive north we stayed in a small hotel close to Petra. The walk through the narrow defile to the extraordinary city carved from rock was a great experience. On the way in, small boys with donkeys were touting for passengers, calling out “Taxi. Taxi”! So, on the return trip we hailed these taxis for a ride back to the village. Jean’s donkey apparently had a new-born foal back at base and set off at high speed to meet her offspring. My donkey, however, was old and had a persistent cough and made the journey slowly. Arriving back before me, Jean, who was without Jordanian money had to settle the bill with a ten-pound note and a ballpoint pen. The next day we visited Little Petra before driving south to have lunch in Aqaba, then over the frontier and back to Eilat.

At Petra, Jordan in 1997

The following year (1998) I attended a meeting of the Society for Research in Biological Rhythms on Amelia Island, Florida, and also undertook another marathon car journey with Jean to the Czech Republic. To get to Amelia Island I first flew to Toronto where I stayed for a day or so with Colin Steel and his wife Xanthe Vafopoulou. We then travelled together from Toronto through Charlotte to Jacksonville, Florida, where we met up with other conference delegates for the final bus ride to Amelia Island. At the conference I organised a session on “Pacemaker Cells in Insects”. The return journey was back through Toronto to London and Edinburgh. In Toronto, the emigration official wanted to know why I had travelled to Florida via Canada instead of directly from London to Miami!

The long drive to the Czech Republic was Jean’s idea – not daunted by our previous marathon to Cracow in 1990. I was to attend the 6th European Congress of Entomology in Ceske Budejovice, and to organise a symposium entitled “Photoperiod, Diapause and Polyphenism”. So we set off on a five-day drive, firstly down to Kent, where we put the car on the train through the channel tunnel, then across northern France, Germany and Austria to the Czech Republic. Whilst crossing France on the autoroute, another car overtook us at high speed and then spectacularly crashed after a burst tyre. A large piece of the burst tyre flew closely over us, just missing our windscreen by what seemed to be a few centimetres. This left us pretty shaken but there was nothing much we could do to help. Across Germany we took to the smaller roads following the “Romantische Strasse” from Würzburg down through a host of pretty mediaeval towns such as Rothenburg to the edge of the Alps at Füssen, where we stayed the night. We then made our way across Austria towards the Czech border and in doing so found ourselves on the Austrian autobahn system. As we were travelling towards the Czech border we became aware that we were being followed – by a police car! The police pulled us over and demanded to see our permit for using the autobahn. When it was ascertained that we did not have such a permit we were escorted to the nearest point at which such a permit could be issued – the Czech border – and threatened with a substantial fine. By the time we reached the border, and finding that the office was closed, we were merely let off with a caution and sent on our way. Having escaped arrest, we continued on our way to Ceske Budejovice, a delightful town that I had visited several times before – and home of one of the finest beers in the world!

Ceske Krumlov 1998, a UNESCO heritage town, near Ceske Budejovice

Our next important trip was in December 1999 to Atlanta, Georgia. I had been invited to a meeting of the Entomological Society of America by David Denlinger who was organising a symposium in honour of Stanley Beck. Jean and I flew out to Atlanta about a week before the meeting, hired a car at the airport and set off on a jaunt south through Georgia to the northern part of Florida. This trip provided some valuable sunshine before returning to Scotland and turned out to be one of the best trips we ever made. After a night in a hotel near the airport we set off south to Warm Springs, where Franklin Roosevelt spent his winters recuperating from polio, before proceeding to Wakula Lodge, just south of Tallahassee where we stayed the night. Our journey then continued down the west coast of Florida to Crystal River where we hoped to see manatees – but without success, apparently because it was “out of season”. The next day we crossed over to stay the night in St Augustine, probably the oldest town in the United States, founded by Spanish settlers, and then up the east coast to Fernandina Beach for the night, and then to Savannah. We found a hotel near the centre of this fascinating old town and were taken on a tour in a white stretch limo! We then returned to Atlanta, via Macon, and settled into the hotel where the meeting was being held.

Some of the delegates at the Atlanta meeting, 1999: Left to right: Maurice and Catherine Tauber, Sinzo Masaki, David Denlinger, me, Steve Reppert, Richard Lee and Michael Chippendale.

The meeting was excellent and David Denlinger gave a fine eulogy of Stanley Beck and his huge contributions to the study of insect photoperiodism. One evening a number of us went out to dinner at a typical “southern” restaurant in Atlanta.

The meal in Atlanta: Mrs Beck, Stanley Beck’s widow, is second from left.