Over the next few years I attended a number of international conferences to report my work on photoperiodism and diapause in Nasonia and Sarcophaga; the most important of these were in Madurai, India (1978), Liege, Belgium (1979), the International Congress of Entomology in Kyoto, Japan, and the Colston Conference in Bristol (1980).

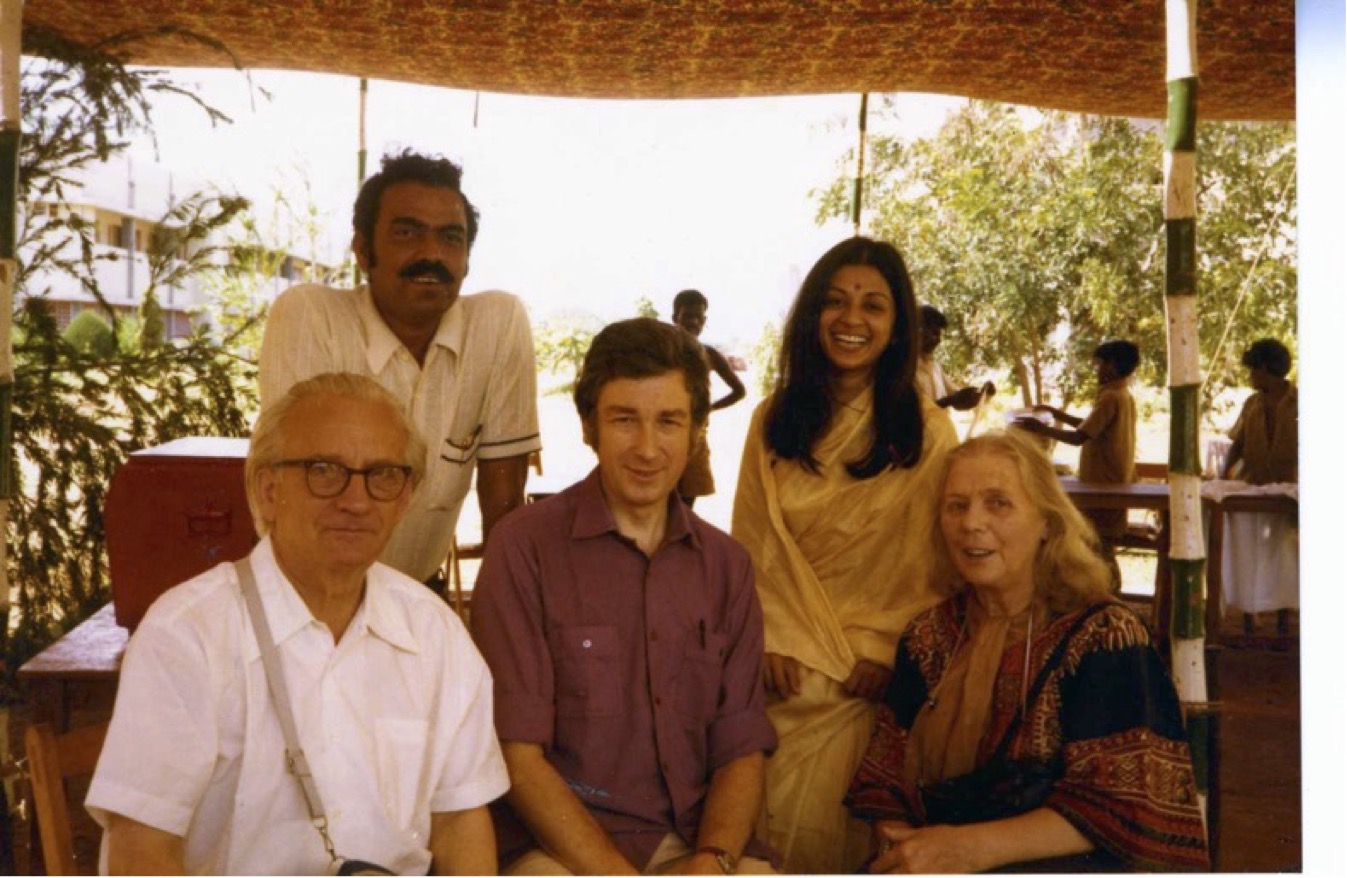

The meeting in Madurai took the form of a summer school organised by M.K. Chandrashekaran, my old friend from Tübingen days, who had moved back to India to set up an Animal Behaviour department at that University. I flew out to Bangalore, staying overnight in Bombay, meeting Shekar, and some of the other teachers and many of the students here. After a day or so in Bangalore we travelled by night bus down to the southern city of Madurai with a near-midnight coffee stop in the town of Salem. Other teachers included Erwin Bünning, who was there with his wife, and Wolfgang Engelmann. We soon found that Tamil Nadu was a ‘dry’ state, the sale and consumption of alcohol being strictly forbidden. However, those teachers arriving through Madras airport found that they could register as having a ‘medical necessity’ for alcohol and could obtain ‘units’ to be exchanged for liquor at international tourist hotels in Madurai. Unlikely as it may seem, a single ‘unit’ could be exchanged for either one bottle of beer or one bottle of an excellent Indian whisky. These ‘units’ became the essential currency during our visit, and our briefcases could be heard clanking with the bottles they contained. In addition, the local food was almost entirely vegetarian – but absolutely delicious. One day the rumour went around that there was some chicken in the large pot - but nothing was ever found despite our efforts! This was my first (and to date, only) visit to the sub-continent, and it left me with many impressions. A lasting memory was going up to some caves at dusk to watch bat behaviour. As the sun went down we crossed paddy fields next to a small village, climbed up a staircase hewn in the rock face past an old Jain temple to the cave entrance, all the while with Indian music coming across from the village. Within minutes of nightfall bats started to come out of the cave, first singly, then in small groups and finally in a swarm, testifying to the extraordinary accuracy of the bat’s circadian clock.

The Chronobiology Summerschool at Madurai, 1978. Front: Erwin Bünning, myself and Frau Bünning. Back: M.K. Chandrashekaran and Asha Chandola.

The meetings in Liege (1979) and Bristol (1980) were less exotic but just as important and memorable. To get to Liege, Jean, Richard and I first drove to Versailles where I met a French colleague, Bernard Dumortier, who was doing work on photoperiodism in the cabbage white butterfly, Pieris brassicae. When we left the Paris area we headed north to the Belgian border staying a night in the Hotel du Gare in Mauberge, a far from salubrious establishment seemingly favoured by the local prostitutes! The next day Jean and Richard headed home, having their own adventure. After picking up my mother in Pinner, they drove north towards Scotland, but the silencer fell off the car. Since it was the August bank holiday Monday, no garages were open, and they completed their journey home in several stages, each stage on the back of a pick-up truck. My journey from Mauberge to Liege was by train, arriving in that city with absolutely no Belgian francs. Perhaps the highlight of this meeting was the generosity of the Belgian brewers who supplied an apparently endless supply of local beers including a range of fruit-flavoured and Trappist brews. On the first night we were all invited to a free beer tasting. There was so much left that a second free beer tasting was arranged for the second night – and then a third! The meeting in Bristol was organised by Brian Follett soon after his appointment to the Chair of Zoology. It was a highly successful international meeting of researchers in all aspects of chronobiology, particularly photoperiodism. The proceedings were published as Biological Clocks in Seasonal Reproductive Cycles.

In 1980 I also travelled to Japan to attend the International Congress of Entomology. We travelled to Tokyo as a group organised by the Royal Entomological Society, and after a night’s recuperation transferred to the bullet train down through Nagoya to Kyoto. I read a paper on my work with Sarcophaga in an excellent session organised by Sinzo Masaki, one of the great men of insect photoperiodism, who I met here for the first time. The session was very well attended by many colleagues and old friends in this field, including Colin Pittendrigh, Jim Truman, Lynn Riddiford, Tony Lees and Dietrich Neumann. One of the highlights of the social programme was a ‘clocks’ dinner at a Japanese fish restaurant where we had to catch our own supper.

Fishing for our supper; Kyoto meeting, 1980.

At each of these meetings I discussed my work on pupal diapause induction in the flesh fly Sarcophaga argyrostoma, briefly reported earlier, in which I used data from the entrainment of the circadian pupal eclosion rhythm as a means to predict the incidence of diapause or nondiapause development within a framework of Pittendrigh’s external coincidence model. These results strongly indicated that photoperiodic induction had its basis in the circadian system, and that an overt rhythm (in this case eclosion) could be used as ‘hands of the clock’ in much the same way that Erwin Bünning had done many years before with leaf movements in the bean plant, Phaseolus. Indeed, the overt eclosion rhythm and the presumed photoperiodic oscillator in Sarcophaga appeared to be so similar that they could have been aspects of the same circadian oscillator. A number of unexplained and troublesome aspects, however, still remained. These included (1) the drop in diapause incidence in very short photophases and in continuous darkness, not predicted by the original form of the external coincidence model, (2) the observation that overt rhythms were a poor measure of photoperiodism in some other species, and (3) that some insects presented data more reminiscent of a non-oscillatory (i.e. non-circadian) dark period timer, resembling an ‘hour-glass’. These apparent anomalies will be addressed later.