My photoperiodism work happened to attract the attention of a number of distinguished workers in the field. At the International Congress of Entomology, held in Moscow in 1968, I met the very distinguished Russian entomologist, Alexander Danilevskii, author of the influential book Photoperiodism and Seasonal Development of Insects. Later, when I read a paper on my research at the Society of Experimental Biology Symposium Dormancy and Survival, held in Norwich in the September of 1968, I met Carroll Williams who invited me to spend a sabbatical at Harvard University. This I would have gladly accepted, but a formal offer was never received; he told me later that funds were unavailable. Then in 1969 I was paid a visit by Jürgen Aschoff, Director of the Max Planck Institute at Erling Andechs near Munich, who was on a lecture tour in the U.K. and always made the point of visiting young research workers in the field. 1971, however, was the high point: in March I was invited to Tübingen by Erwin Bünning and Wolfgang Engelmann to participate in a meeting on photoperiodism, and later that year I received the invitation to Stanford from Colin Pittendrigh which, as recounted above, I accepted with alacrity.

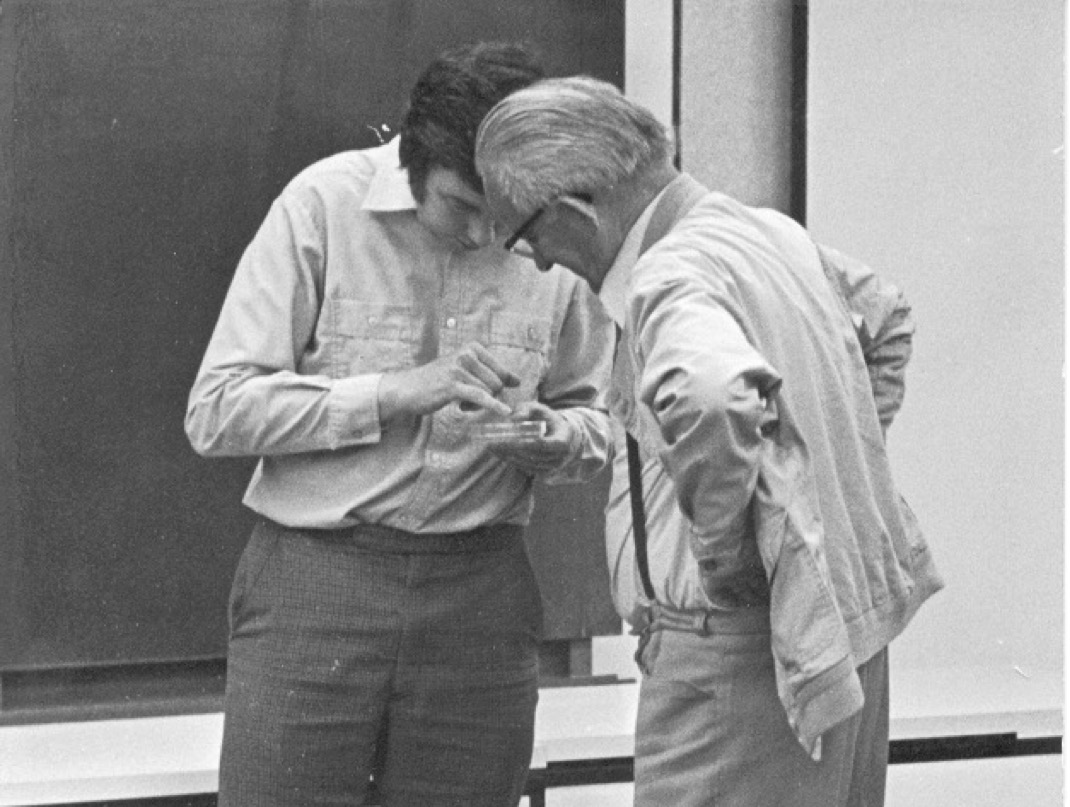

The meeting in Tübingen was held in early March 1971. It was here that I met Erwin Bünning for the first time, and also others in the Tübingen group including Wolfgang Engelmann, M.K. Chandrashekaran (Shekar) and many of the German chronobiologists. Shekar and I got on particularly well, and he showed me many of the ‘sights’ around this beautiful town. Although almost spring, the weather was intensely cold. I well remember waiting for bus on the bridge over the Neckar in a snow storm with the temperature plunging below zero. Also present at that meeting was Art Winfree, one-time student of Pittendrigh’s and by now moved to Purdue University. He had driven from Sussex, where he was on sabbatical, in a small Morris Mini, only to have his engine freeze solid in Tübingen. Art reported on his highly original work on the eclosion rhythm in Drosophila pseudoobscura in which he showed that a short light pulse (about 45 seconds) of a particular intensity blue light, placed at a critical phase, could apparently ‘stop the clock’ as though it were hitting the oscillation’s singularity. Although sometimes controversial, this work had a long-lasting influence on many researchers in the field, and later I was able to replicate it for the pupal eclosion rhythm of the flesh fly, Sarcophaga argyrostoma. A few weeks later I was to meet many of these scientists again at a meeting organised by Jan de Wilde at Wageningen in the Netherlands.

Showing Erwin Bünning Nasonia vitripennis in Tübingen, 1971

I made the first of my many trips to the United States in September 1970, mainly to read a paper on reproductive physiology of Glossina at the International Congress of Parasitology, held that year in Washington D.C. However, after one night in New York, I left the group of delegates to stay with Kingsley Sanders, Jean’s old ‘boss’ from the Virus Research group at the London School of Hygiene, who had moved to the Sloan Kettering Institute. This gave me the opportunity to look around New York and to recover a bit from jet lag. I then took a Greyhound bus up to Boston to visit Carroll Williams at Harvard. A short taxi ride over the Charles River to Cambridge soon found me at the University and to Carroll’s office in the basement of the Biology building. He greeted me, as with all his guests, with a test of character – a very hot chilli. This I passed with ease, loving anything spicy! I was also greeted with an announcement from the others in Carroll’s research group that Jim Truman and Lynn Riddiford were about to get married, even though that was the first occasion we had met. Jim and Lynn, together with Bill Bradshaw, became life-long friends. I stayed with Carroll and his wife Muriel at their home close to Cambridge, and then travelled the next day back to New York and then Washington, again by Greyhound bus, to re-join the Congress.

My second visit to the States was to take up the offer from Colin Pittendrigh to spend a sabbatical with him at Stanford University. Entry into the United States for a sabbatical meant that I had to present a full-frontal X-ray of my chest to prove that I did not have tuberculosis. I also needed to take with me living specimens of Sarcophaga argyrostoma and Nasonia vitripennis. To do this I was advised to contact the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to seek permission for the importation of living insects. This permission was eventually granted, but on the understanding that I carried the insects separately from my luggage in a small parcel, and presented them, together with the by now lengthy documentation to the immigration officers. Early in October 1971, almost immediately after returning from Rhodesia, I flew over to New York. When I reached immigration the officer in charge seemed particularly unconcerned about my living material. After explaining that they were maggots, and producing the relevant documents, he merely said “are you going fishing?” - to which I just answered “yes” and proceeded into the United States with my small package of Sarcophaga pupae, some parasitised by Nasonia. Such was the state of airport security in those pre-9/11 days.

In New York I stayed once more with Kingsley Sanders and his wife Irene. Kingsley and I drove out to Little Neck on Long Island where the family of one of his colleagues at the Sloan Kettering lived in a large house. The family owned a major film production company and we were treated to a private showing of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning starring Peter Finch, in their small viewing room, with an ample supply of gin and tonic. Working as an au pair for the family was the daughter of Joshua Nkomo; unfortunately when she heard that I had only just returned from Rhodesia she assumed that I must be a supporter of the white supremacist regime of Ian Smith, and declined to meet me. Later in the day, a walk in the autumn sunshine around their property introduced me to two of the ‘must-see’ experiences for a Zoologist. The beach was covered with the (at that time of the year) mainly dead carcases of the horseshoe ‘crab’, Limulus, a living fossil of an animal I had only previously seen pickled in a glass jar. The second was the sight of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) on their autumnal migration south to their over-wintering sites in Mexico.

Over the Bear Tooth Pass to Wyoming, October 1971

After a few days in New York I boarded a flight to Billings, Montana, where I was met by Colin Pittendrigh and one of his Ph.D. students, Pat Caldarola. We drove from the airport through Red Lodge and then over the 10,000 foot Bear Tooth pass, through snow banks on either side of the road, to the Pittendrighs’ lock-log cabin on the Clarks Fork, just north of the Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. Pitt and his wife Mikey had been up in the Clarks fork for several weeks, him to get some well deserved time for writing, and they intended to stay there for a while despite the early onset of winter in those parts. We made several hikes in the surrounding hills and, of course, paid a visit to the Yellowstone, seeing ‘Old Faithful’, Pitt’s favourite trout stream (the Fire Creek), herds of buffalo, grizzly bears and everything else that a good tourist should see. We then left the cabin, camping on the way to Jackson’s Hole near the Grand Tetons. Here we boarded a plane to San Francisco, leaving Mikey to return to the Clarks Fork. From the airport in San Francisco we drove to Palo Alto where I stayed at Pitt’s house until suitable accommodation was obtained for me in a studio apartment in nearby Mountain View. At first I borrowed Pitt’s bike to get me to work, then drove his Chevrolet Camaro until I purchased my own car, a 1966 Mercury Commuter. One day I was followed all the way home by another car. When I got back to my apartment the driver announced that the car had once belonged to his father, the fire chief of Palo Alto, but had been ‘totalled’ in a road crash! Although the car was presumably made up from several pieces, it served me well until my departure in the late summer of 1972.

The Pittendrigh’s log cabin in the Clark’s Fork, Wyoming

In the Biology department at Stanford, Pitt’s group occupied the basement area. I had agreed to offer a course of 22 lectures on Insect and Man as Human Biology 104. When I arrived in the department I was asked how many lectures would I like, how many students, where I would like to hold the lectures, and at what time? This was a very different experience to teaching in a British University where everything like this is decided by a committee. Since I had no very strong views on these matters, I ended up giving my lectures at 8:30 a.m. in the basement of the Psychology building to about 80 undergraduates. At first I was understandably a bit nervous and the students were amused at my British accent, but I kept my numbers well up (the criterion for success apparently) and the course was not terminated. It was when I had to ‘grade’ the examinations that I got into more difficulty. No-one had explained to me that in American Universities the full marking scale was used (up to 100 per cent). Consequently I awarded the very best students marks of 70 to 75 per cent, equivalent of a good ‘first’ in the U.K., but only a C grade in the U.S.! Since many of the students needed an A grade to get into medical school, I had to do a rapid re-think and undertook an extensive re-marking exercise. Everyone seemed happy in the end!

The Biology building at Stanford, California in January 1972

In the laboratory I established cultures of Sarcophaga and Nasonia, although I don’t think that other members of the Biology department really appreciated the malodorous emanations from the rotting meat used as maggot food! The departmental machine shop, led by one Bert Bubb, an émigré Welshman, constructed some ingenious ‘clocks’ that enabled me to expose cultures of maggots and wasps to photo-cycles varying from about 20 hours to more than 72 hours, each cycle containing a ‘short’ light phase of 10 to 14 hours combined with a long and variable period of darkness. Thus, I was able to perform so-called ‘resonance’ experiments, previously begun in Edinburgh, to test whether circadian rhythms were involved in photoperiodic timing. The rationale behind such experiments was thus: by systematically varying the overall period of the light-dark cycle from 20 to over 72 hours, the light ‘came on’ at different times after the onset of darkness in each experimental group. Therefore, if there was a particular light-sensitive phase occurring with a circadian (near 24 hour) frequency in the extended ‘night’, as predicted by Bünning’s hypothesis, the light pulses would alternately hit or miss these phases giving rise to an apparent circadian rhythm of long or short-day effect. In both species this was the outcome of these experiments, strongly suggesting that the circadian system was somehow involved in photoperiodic timing.

After a few weeks in Palo Alto, Pitt, Phil Sokolove and I headed off for Washington D.C. to attend the Second Conference on Biochronology, held in an eighteenth century mansion, then the Belmost Conference Center, at Elkridge, Maryland. This was a small meeting addressed to the problem of how to bridge the apparent gap between formal approaches to photoperiodism and our more concrete knowledge of insect endocrinology. The delegates sat around a large table and just talked: formal lectures were not on the agenda. Everything that was uttered was taken down verbatim with a view to eventual publication. But when we finally received the transcripts of our talks they turned out to be rather rambling and incoherent, and the proposed book never saw the light of day! I am not sure that we achieved our objective either, although it did bring together scientists working in apparently disparate disciplines. After the conference I travelled by train to Trenton, New Jersey, and then by bus to Princeton to visit Dolly Minis, Pitt’s erstwhile research colleague, with a view to discussing our collaboration in writing a review for a second edition of The Physiology of Insecta, edited by Morris Rockstein. In the end, Dolly declined to participate, and Pitt handed the project over to me saying that he wanted a rest from all this writing. After this short stay I proceeded, again by bus, into New York, and then flew back to San Francisco. Before Christmas 1971 Pitt returned to the cabin in the Clarks Fork and promptly got snowed in for the winter, not appearing in Stanford for several weeks. During that time Phil Sokolove and I seemed to be in charge of the research group!

In the spring of 1972 I was invited to give a lecture on tsetse flies at the University of California at Davis, near Sacramento. On the drive there I had a small adventure. Taking the wrong turning up a rather narrow road, I attempted a three-point turn and found my rear wheels spinning in the gravel over a rather deep ditch. Literally with minutes, however, a fork-lift truck appeared from nowhere and lifted me clear of the ditch! At Davis I had an interesting conversation with the great evolutionary geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky who had been Colin Pittendrigh’s Ph.D. advisor at Columbia University just after the war.

At the end of March it was the time for Jean and the boys to come out to California. We had agreed that Jean would stay behind in Edinburgh for the first six months of my sabbatical, mainly to avoid too much disruption to the boys’ education. I could never have gone to Stanford had Jean not been so willing and, once again, I owed her a considerable debt. In March I had located a suitable house at 4, Aliso Way in nearby Ladera, and approached local schools for the boys to attend for the few remaining weeks before the summer recess. They flew out to New York at the end of March, staying for a day or so with Kingsley and Irene Sanders. They then continued to San Francisco where I met them at the airport. Richard celebrated his eighth birthday partly in New York and partly in San Francisco! Going to school in the United States seemed to suit the two elder boys, although Michael objected strongly to having to sit next to girls! Robert probably got the most from the experience, even taking a course on aeronautical engineering, which apparently consisted of making paper aeroplanes! Richard, however, benefited less from the experience, and we kept him at home for the few remaining weeks of the semester.

Having the family with me meant that we took off to travel around the West, visiting Muir woods and the giant redwoods. That summer we took a longer trip to Disneyland in Los Angeles. We then set out across the Mojave Desert through Barstow, Calico ghost town, and the aptly named Baker, to Las Vegas. Here we camped for the night even though the temperature at midnight was still 104 °F. “Too much body heat” announced Michael, so we took to sleeping outside on top of the picnic tables. Our trip also took in the north rim of the Grand Canyon and an attempt to reach the Zion National Park which was thwarted by a severe cloudburst. Our return journey took us up to Beatty, Nevada, where we had the cheapest ever motel ($12 for the entire family!); we then crossed Death Valley soon after dawn, while it was still cool, and headed north to Mono salt lake before going home to San Francisco through the Yosemite National Park.

Across the Nevada desert, 1972

When the time came for us to leave Stanford, we sold the car – to the garbage man who had a very large family – settled up with the IRS, and headed home to Edinburgh. The boys went back to school and we settled down once again to family life. 1973 was a quiet year, the highlight of which was my promotion to a Readership in the University.

In 1974 we went as a family to Tübingen for six weeks, both for a holiday and for me to do a little science. We drove down to the channel ports, made a rather rough crossing on a Hovercraft, and stayed a night with Dietrich Neumann and his wife near Cologne, and with Klaus Brinkmann and his family near Bonn. In Tübingen we stayed in a variety of places including a small hotel near the swimming baths and the Max Planck Institute. In the lab I tried to record circadian pupal eclosion rhythms in Nasonia vitripennis but with little success; the holiday, however, was a great success! Thus the decade from 1965 to 1975 came to a rather quiet conclusion.

Tübingen in 1974